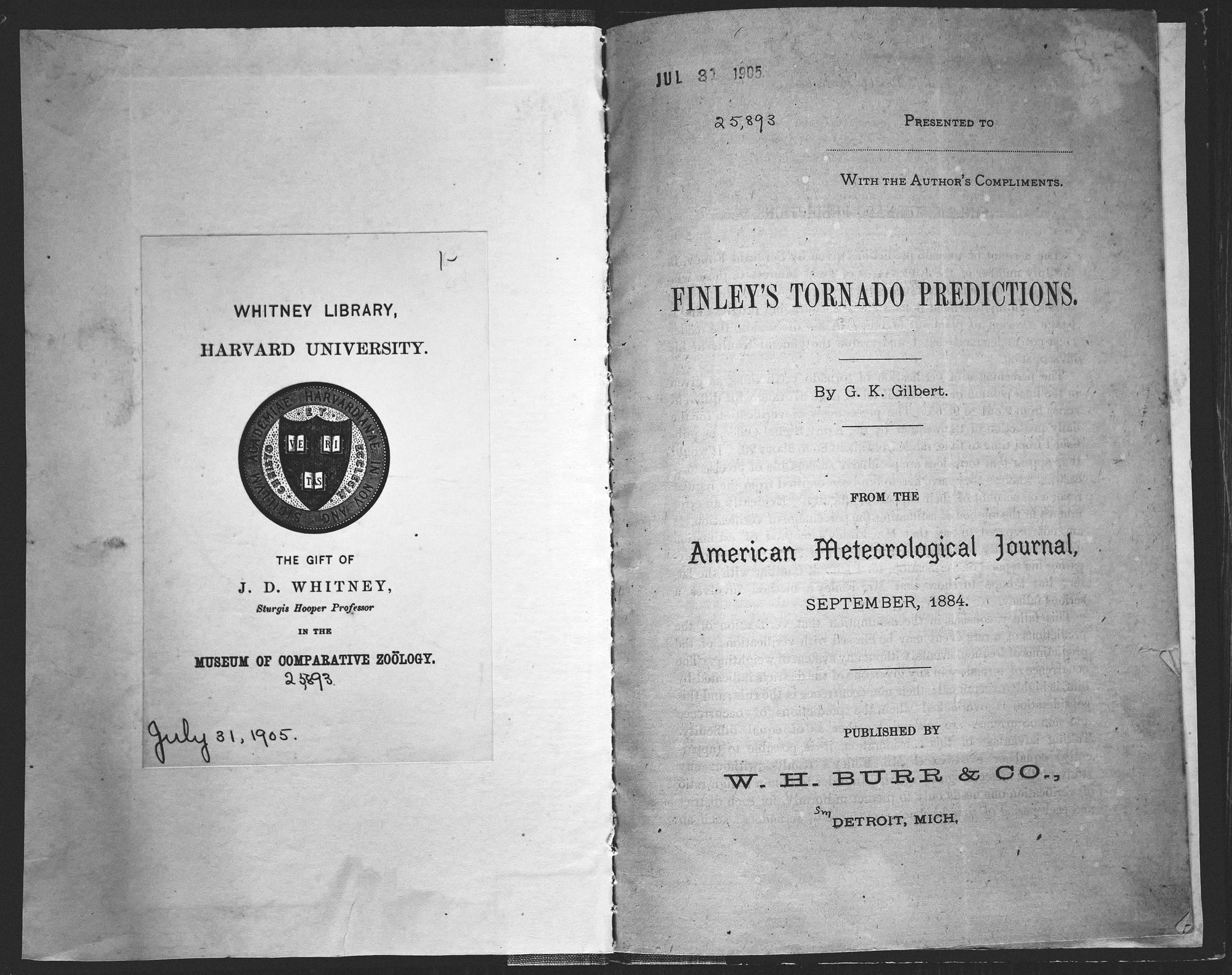

Library Series - "Finley's Tornado Predictions"

First off, thanks for the awesome feedback on the first post of the historical collection! It’s a lot of fun getting to share the history of these things and discuss them with friends and colleagues, and there’s always something to be learned by looking back at where we came from. Today’s entry isn’t necessarily a coveted or even widely known piece of scientific literature, and in terms of rarity, I’ve seen maybe 2 or 3 other copies floating around for purchase out there if you know what to look for. However, what does make this one fun and unique is that much like the last article, “Tornadoes and Derechoes”, this publication is a part of a broader discourse around the work of none other than John Park Finley himself.

Once again, I’m going to put off the detailed biography of Finley and his work for a later post (or two) and I promise it’ll be worth the wait, but for now, all you need to know is that John Park Finley is considered to be the first serious tornado researcher in the United States. In spite of pioneering some of the first tornado climatologies and coming up with an ingredients-based approach to forecasting tornadoes 60 years before Earnest J. Fawbush and Robert C. Miller would do so, Finley was a controversial figure who often didn’t quite get things right. In “Tornadoes and Derechoes”, it was the fact that he was classifying long-lived straight-line wind events as tornadoes. In today’s article, the argument is over Finley’s claim to be absurdly accurate at predicting tornadoes, claiming a success rate of 95-98%. This, and the subsequent journalistic refutation of Finley’s verification method by Gilbert, directly resulted in the pioneering of forecast verification metrics and skill scores that are still used today in either practice or principle.

As I did in the last article, and will continue to try and do for everything I can, here is a scanned PDF of the article being discussed if you’d like to read it for yourself. You can download it here.

Grove Karl Gilbert - Geologist

G. K. Gilbert graduated from The University of Rochester in 1871, became a surveyor out West working primarily in the Rockies. After the creation of the U.S. Geological Survey, he was appointed Senior Geologist and worked for the USGS until his death, including a stint as its director. He is to this day the only geologist who has been twice elected as President of the Geological Society of America. Gilbert was also a pioneer in the fields of geomorphology and planetary science, studying impact craters and conducting experiments on meteorite impacts. Needless to say, Gilbert was a highly regarded and successful scientist in his day and field. I’m not entirely sure what motivated him to pen an article in the American Meteorological Journal on the verification of tornado forecasts, but I suppose it was much more common in that day and age for scientists to be more cross-discipline in their projects. Perhaps it was their mutual roles as government scientists - Finley in the Signal Corp, and Gilbert in the USGS. I suppose we won’t know for sure, and I couldn’t find anything out there that explains or links reasoning for Gilbert to become interested in the subject… so if anyone comes across anything, let me know and I’ll update it to go here!

What is a Skillful Tornado Forecast?

After conducting his climatologies and research into what patterns precede tornado occurrences, Finley began making his own predictions and computing his verification rather naively. In short, Finley counted a correctly forecast null-event (a day without tornadoes that was forecast to not have tornadoes) the exact same as a positive tornado forecast (a day with tornadoes that was forecast to have tornadoes). Because of the overall rarity of tornadoes and the weather patterns that precede them, this meant that Finley recorded the absurdly high verification ratings of 95-98% accuracy. This is because over 90% of the time in a given year, it’s a safe bet to say there will not be a tornado in a particular location at a particular time. It should become quite obvious and clear that you cannot verify the forecasts of rare phenomena in this way - and that’s what Gilbert set out to show. Unlike Hinrichs in “Tornadoes and Derechoes”, however, Gilbert did not view Finley’s work with contempt. Quite the opposite, Gilbert was looking to help improve the process of verification as a whole.

The account of tornado predictions given by Sergeant Finley, in the July number of the Journal, is of great interest to those who are sanguine of the ultimate successful forecasting of these destructive storms. In my judgment it shows encournging progress, and if I take occasion to point out a fallacy in his discussion, the reader must not understand that I undervalue the general results of his investigation.

…

This fallacy consists in the assumption that verification of the predictions of a rare event may be classed with verifications of the predictions of frequent events, without any system of weighting. The occurrence of tornadoes in any given one of the districts indicated by him, is highly exceptional; their non-occurrence is the rule; and this consideration is overlooked when the predictions of occurrence and non-occurrence are classed together as of equal difficulty. Taking ndvantage of this considerntion, it is possible to (apparently) equal or even excel Mr. Finley’s results, without any study of the meteorological record. In order to obtain a high ratio of verification, one needs only to predict uniformly for each district and ench period of time, the non-occurrence of tornadoes; such an assumed indiscriminating prediction gives for each of the periods published in his article, a higher average verification than claimed by him.

The Gilbert Skill Score

Gilbert was kind enough to do more than just point out a fallacy in the way Finley was conducting his verification, but proposed a solution that is more mathematically and statistically sound for this kind of forecast. While not presented in table form, what Gilbert proposed is rather close to what we know today as a Contingency Table. The Gilbert Skill Score is almost identical to the well-known Critical Success Index, but it also takes into account “hits due to chance”. In contingency table notation (e.g. A, B, C table notation), the Gilbert Skill Score takes on the following form:

GS = (A-CH)/(A+B+C-CH), where CH = Chance Hits

To calculate CH, you take event frequency multiplied by the number of event forecasts. The Gilbert Skill Score is considered to the the unbiased version of the Critical Success Index.

With this metric, John Park Finley’s tornado prediction rate is more around 21-23% accurate. While that sounds much less impressive than the quoted 93%+ hit rate, as with all verification metrics, it needs a baseline comparison. Often times this is done by comparing a forecast’s skill metric to the skill of a forecast that uses climatology to make its prediction, and then comparing that skill score to the forecast skill score. Unfortunately as of the time of writing this, I cannot find any average numbers on the skill of climatology for tornado forecasts. To make it a one-to-one comparison you’d also need to limit it to the climatology for the years of Finley’s verification, and limit it geographically to match his predictions as well, but intuition tells me that Finley’s success would be either comparable to climatology or slightly lower since he was using his climatology to make these forecasts. Perhaps that would be a fun project for another day - compute the contingency tables for the 1880s using Finley’s tornado climatologies and compare his Gilbert Skill Score to climatology!

That’s A Wrap

I hope this has been an enjoyable deep dive into another journalistic discourse - I find stuff like this and the Hinrichs study fascinating because of the dialogue that surrounds the research. On the one hand, Finley didn't always have the most sound methods or understanding, but if it were not for him pushing the envelope and taking some risks along the way, it's hard to say if the people like Hinrichs or Gilbert would have been as motivated to take a crack at these subjects. Even though it was published in 1884, the mathematical and statistical principles still apply and are actively used in today's research. In fact, I used many of these skill scores myself when evaluating the performance of numerical weather forecasts of severe weather back at OU! So it's kind of cool to own a piece of the scientific history that brought forth this technique and knowledge.

As always - if you’re enjoying this, feel free to let me know in the comments or on Twitter. I have many more historical documents to share, and may even have a guest writer appear here to share from his collection. Until then, thanks for stopping by!